ADAPTING ASIAN FOLKLORE AS A BASIS FOR

CHILDREN’S AND YA LITERATURE

Introduction

If you take a close look at children’s

books, many are based on fairy tales (either in terms of the plot/sub-plot or it

contains an idea, or a motif from an ancient source). Fairy tales themselves

spring from folklore. Not surprising as these stories are rooted in

the society and culture they come from. I also believe that almost all folk

tales are based on real life; events which have etched themselves into the

collective memory of a group of people. Of course they have been embellished

over the years and centuries through numerous retelling but it is the nature of

oral traditions that a story gets altered by the story teller to become

relevant for the time and place they are being retold. Stories became fixed

only when publishing and printing became available.

If you take a close look at children’s

books, many are based on fairy tales (either in terms of the plot/sub-plot or it

contains an idea, or a motif from an ancient source). Fairy tales themselves

spring from folklore. Not surprising as these stories are rooted in

the society and culture they come from. I also believe that almost all folk

tales are based on real life; events which have etched themselves into the

collective memory of a group of people. Of course they have been embellished

over the years and centuries through numerous retelling but it is the nature of

oral traditions that a story gets altered by the story teller to become

relevant for the time and place they are being retold. Stories became fixed

only when publishing and printing became available.

Slide 2.1: Illustration of Sembilan of the Rice Fields, from Timeless Tales of Malaysia

- Dressing Old Tales in New Clothes

*The

Owl Service, (1967) by Alan Garner

An excellent example of a book based on an

old myth is Alan Garner’s The Owl Service.

This award-winning book in a sense relives an old legend dressed in modern

clothes. Garner’s book is about three teenagers who are thrown together by

circumstance and became caught up in a love triangle from an ancient Welsh

legend – of Lleu Llaw Gyffes, and his wife Blodeuwedd, a woman made from the

flowers of broom, meadowsweet and oak. She was conjured from the essence of

these flowers by Lleu’s uncle, the wizard Gwydion. Later, she fell in love with

Gronw Pebr, and together, they conspired

to murder Lleu. Gronw mortally wounded Lleu with a spear but he escaped death

by turning into an eagle. Lleu’s uncle, Gwydion tracked the eagle down and

healed him. Lleu demanded revenge and by

magic, he and Gronw exchanged places. Lleu killed Gronw by throwing a spear

with such force that it went through a rock behind which Gronw was hiding. For

her part in her husband’s murder, Blodeuwedd was turned into an owl by Gwydion,

a fate ‘worse than death’ we are told. In

The Owl Service, Alison is Bloduewedd,

Gwyn is Lleu and Roger is Gronw. We learn that Gwyn’s ancient ancestors

probably owned the valley even though his mother works as housekeeper for Alison’s

mother and her stepfather, Clive Bradley (Roger’s father).

An excellent example of a book based on an

old myth is Alan Garner’s The Owl Service.

This award-winning book in a sense relives an old legend dressed in modern

clothes. Garner’s book is about three teenagers who are thrown together by

circumstance and became caught up in a love triangle from an ancient Welsh

legend – of Lleu Llaw Gyffes, and his wife Blodeuwedd, a woman made from the

flowers of broom, meadowsweet and oak. She was conjured from the essence of

these flowers by Lleu’s uncle, the wizard Gwydion. Later, she fell in love with

Gronw Pebr, and together, they conspired

to murder Lleu. Gronw mortally wounded Lleu with a spear but he escaped death

by turning into an eagle. Lleu’s uncle, Gwydion tracked the eagle down and

healed him. Lleu demanded revenge and by

magic, he and Gronw exchanged places. Lleu killed Gronw by throwing a spear

with such force that it went through a rock behind which Gronw was hiding. For

her part in her husband’s murder, Blodeuwedd was turned into an owl by Gwydion,

a fate ‘worse than death’ we are told. In

The Owl Service, Alison is Bloduewedd,

Gwyn is Lleu and Roger is Gronw. We learn that Gwyn’s ancient ancestors

probably owned the valley even though his mother works as housekeeper for Alison’s

mother and her stepfather, Clive Bradley (Roger’s father).- Using Folktales as an Integral Part of the Plot

This

brings us to three books called the Chronicles of Old Japan by Australian author,

Ruth Manley. I believe she would have written more books but unfortunately, she

passed away in 1986, so we are left with only three wonderful books.

- The Plum Rain Scroll, 1978

- The Dragon Stone, 1982

- The Peony Lantern, 1987

Ruth

Manley’s books are steeped in Japanese folklore and extremely entertaining to

read. They peopled by eccentric lords and ladies, samurai and ninja and also

creatures from Japanese folklore such as nishu, baku, onni etc. Manley

incorporates characters, ideas and storylines taken from Japanese folklore

directly into her stories. According to a commentary I read on her books, Manley’s

books most closely resembles Llyod Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain, which are

based on Welsh folklore.

Slide 5.1: Cover of old

Plum Rain Scroll

The

Plum Rain Scroll is a magical scroll which is

written in the ‘old language’. It contains three great magic – the secret of

immortality; the secret of turning baser metal into gold (similar to the

philosopher’s stone) but most important of all, the ‘unanswerable word’ - word

with the power to render all who hear it powerless to resist. The main

protagonist is an odd-job boy called Taro, a foundling who helped his Aunt Piety

to run an Inn called the Tachibana-ya. Aunt Piety is actually a fox-woman who has

magical powers, she is also married to Uncle Thunder, an eccentric and

absent-minded inventor who could be one of the Emperor’s son. Taro is thrown

into the fray when the evil warlord, Lord Marishoten, and his Black Warriors

attempted to capture Aunt Piety, she being the only person in the land who can

still read the ‘old language’. Along the way to rescue his aunt, Taro meets up

and form allegiances with a motley crew of friends including Prince Hachi, the

legendary prince eight-thousand spears; a travelling troupe whose members

include Oboro, the Cherry Blossom Princess; the ghost of a young samurai called

Hiroshi (who was murdered by Marishoten); and Mouse also known as Lord Sweet

Potato, a high-born nobleman who has a dream-eater called Baku, for a pet and

so on. In the first book, Ruth Manley throws in almost every imaginable

creature you could encounter in Japanese folklore into her book including the

Tengu of Vast Supernatural Wisdom! Taro and his friends race against Marishoten

and his henchmen to locate the Plum Rain Scroll, with only an old riddle to

guide them. Towards the end, Taro discovers that Oboro was a real princess.

The

Plum Rain Scroll is a magical scroll which is

written in the ‘old language’. It contains three great magic – the secret of

immortality; the secret of turning baser metal into gold (similar to the

philosopher’s stone) but most important of all, the ‘unanswerable word’ - word

with the power to render all who hear it powerless to resist. The main

protagonist is an odd-job boy called Taro, a foundling who helped his Aunt Piety

to run an Inn called the Tachibana-ya. Aunt Piety is actually a fox-woman who has

magical powers, she is also married to Uncle Thunder, an eccentric and

absent-minded inventor who could be one of the Emperor’s son. Taro is thrown

into the fray when the evil warlord, Lord Marishoten, and his Black Warriors

attempted to capture Aunt Piety, she being the only person in the land who can

still read the ‘old language’. Along the way to rescue his aunt, Taro meets up

and form allegiances with a motley crew of friends including Prince Hachi, the

legendary prince eight-thousand spears; a travelling troupe whose members

include Oboro, the Cherry Blossom Princess; the ghost of a young samurai called

Hiroshi (who was murdered by Marishoten); and Mouse also known as Lord Sweet

Potato, a high-born nobleman who has a dream-eater called Baku, for a pet and

so on. In the first book, Ruth Manley throws in almost every imaginable

creature you could encounter in Japanese folklore into her book including the

Tengu of Vast Supernatural Wisdom! Taro and his friends race against Marishoten

and his henchmen to locate the Plum Rain Scroll, with only an old riddle to

guide them. Towards the end, Taro discovers that Oboro was a real princess.

Slide 6.1: Cover of new

Plum Rain Scroll

The

Dragon Stone – Another antagonist emerges in the

second book. She is the Jewel Maid and it turns out that Lord Marishoten is

actually her servant. The Jewel Maid is based on an old Japanese legend – that

of Tamano, a beautiful and ancient nine-tailed fox demon. In folklore, Tamano bewitched the Emperor and sought

to destroy the Imperial line until her true identity was discovered and she was

driven out. She sought refuge in a black stone which came to be known as the

Death Stone. In the book, the Dragon Stone has the power to bend the will of

people; it was created by the Jewel Maid. Manley incorporates an iconic

Japanese folktale, the Taketori

Monogatari into this book. To

summarise: A poor bamboo cutter finds a shining child (and nuggets of gold) in

the stump of a large bamboo. He takes her home to his wife and they raise her

as their own child. She is known as Kaguyahime and grows up into an

accomplished and amazing beauty. Her five most illustrious suitors are each

given an impossible task to win her hand. In The

Dragon Stone, Kaguyahime is sent to earth for the express purpose of

locating the Dragon Stome to prevent it from falling into the hands of the

Jewel Maid again. As in the folktale, Otomo no Miyuki was given the task of

obtaining the Dragon Stone. In this he succeeds but he falls under the stone’s influence

and triggers off the Genpei Wars (a real historical event). It falls to Taro,

Oboro and friends including Prince Hachi to locate and unmake the Dragon Stone,

again guided by a riddle.

The

Dragon Stone – Another antagonist emerges in the

second book. She is the Jewel Maid and it turns out that Lord Marishoten is

actually her servant. The Jewel Maid is based on an old Japanese legend – that

of Tamano, a beautiful and ancient nine-tailed fox demon. In folklore, Tamano bewitched the Emperor and sought

to destroy the Imperial line until her true identity was discovered and she was

driven out. She sought refuge in a black stone which came to be known as the

Death Stone. In the book, the Dragon Stone has the power to bend the will of

people; it was created by the Jewel Maid. Manley incorporates an iconic

Japanese folktale, the Taketori

Monogatari into this book. To

summarise: A poor bamboo cutter finds a shining child (and nuggets of gold) in

the stump of a large bamboo. He takes her home to his wife and they raise her

as their own child. She is known as Kaguyahime and grows up into an

accomplished and amazing beauty. Her five most illustrious suitors are each

given an impossible task to win her hand. In The

Dragon Stone, Kaguyahime is sent to earth for the express purpose of

locating the Dragon Stome to prevent it from falling into the hands of the

Jewel Maid again. As in the folktale, Otomo no Miyuki was given the task of

obtaining the Dragon Stone. In this he succeeds but he falls under the stone’s influence

and triggers off the Genpei Wars (a real historical event). It falls to Taro,

Oboro and friends including Prince Hachi to locate and unmake the Dragon Stone,

again guided by a riddle. The

Peony Lantern incorporates several legends and

myths into its storyline. Even the title of the book refers to an eerie

Japanese ghost story. A central subplot is the story of Ho-Wori and the

Princess of the Sea (this is a myth I retold in my book ‘Eight Treasures of the Dragon’ as ‘Ho-Wori and the Princess of the

Sea’). It is the story of two brothers Ho-Wori (Prince Fire Fade) and Ho-Deri (Prince

Fire Flash) who are bitter rivals. One day, Ho-Wori gets lost at sea and is

taken to the place of the Sea king. He falls in love with the sea king’s

daughter and marries her. After what seems only a few weeks, he is overcome

with homesickness and decides to return home. He is given a treasure chest and

two magical pearls as gifts by the sea king. In the book, The Jewel Maid and Lord

Marishoten reemerge, but this time they are seeking the objects of power known

as the windflowers. No one actually knew what the windflowers were until the

emperor suddenly remembered his youth and his visit to the kingdom of the sea (he

was actually Ho-Wori or Prince Fire Fade). In any case, he realised that the windflowers

were actually the two pearls – the tide-ebbing and the tide-flowing pearls - which

had been given to him by the sea king. Unfortunately, the Jewel Maid had cast a

spell on him and he had fallen into a deep sleep and is unable to convey his

knowledge to anyone. Meanwhile, The Jewel Maid kidnaps Oboro, believing that

she has the windflowers. Ruth Manley successfully incorporated this old myth

into an integral part of the story.

The

Peony Lantern incorporates several legends and

myths into its storyline. Even the title of the book refers to an eerie

Japanese ghost story. A central subplot is the story of Ho-Wori and the

Princess of the Sea (this is a myth I retold in my book ‘Eight Treasures of the Dragon’ as ‘Ho-Wori and the Princess of the

Sea’). It is the story of two brothers Ho-Wori (Prince Fire Fade) and Ho-Deri (Prince

Fire Flash) who are bitter rivals. One day, Ho-Wori gets lost at sea and is

taken to the place of the Sea king. He falls in love with the sea king’s

daughter and marries her. After what seems only a few weeks, he is overcome

with homesickness and decides to return home. He is given a treasure chest and

two magical pearls as gifts by the sea king. In the book, The Jewel Maid and Lord

Marishoten reemerge, but this time they are seeking the objects of power known

as the windflowers. No one actually knew what the windflowers were until the

emperor suddenly remembered his youth and his visit to the kingdom of the sea (he

was actually Ho-Wori or Prince Fire Fade). In any case, he realised that the windflowers

were actually the two pearls – the tide-ebbing and the tide-flowing pearls - which

had been given to him by the sea king. Unfortunately, the Jewel Maid had cast a

spell on him and he had fallen into a deep sleep and is unable to convey his

knowledge to anyone. Meanwhile, The Jewel Maid kidnaps Oboro, believing that

she has the windflowers. Ruth Manley successfully incorporated this old myth

into an integral part of the story. - Using a Quest or a Journey to retell Folktales and Construct a Story

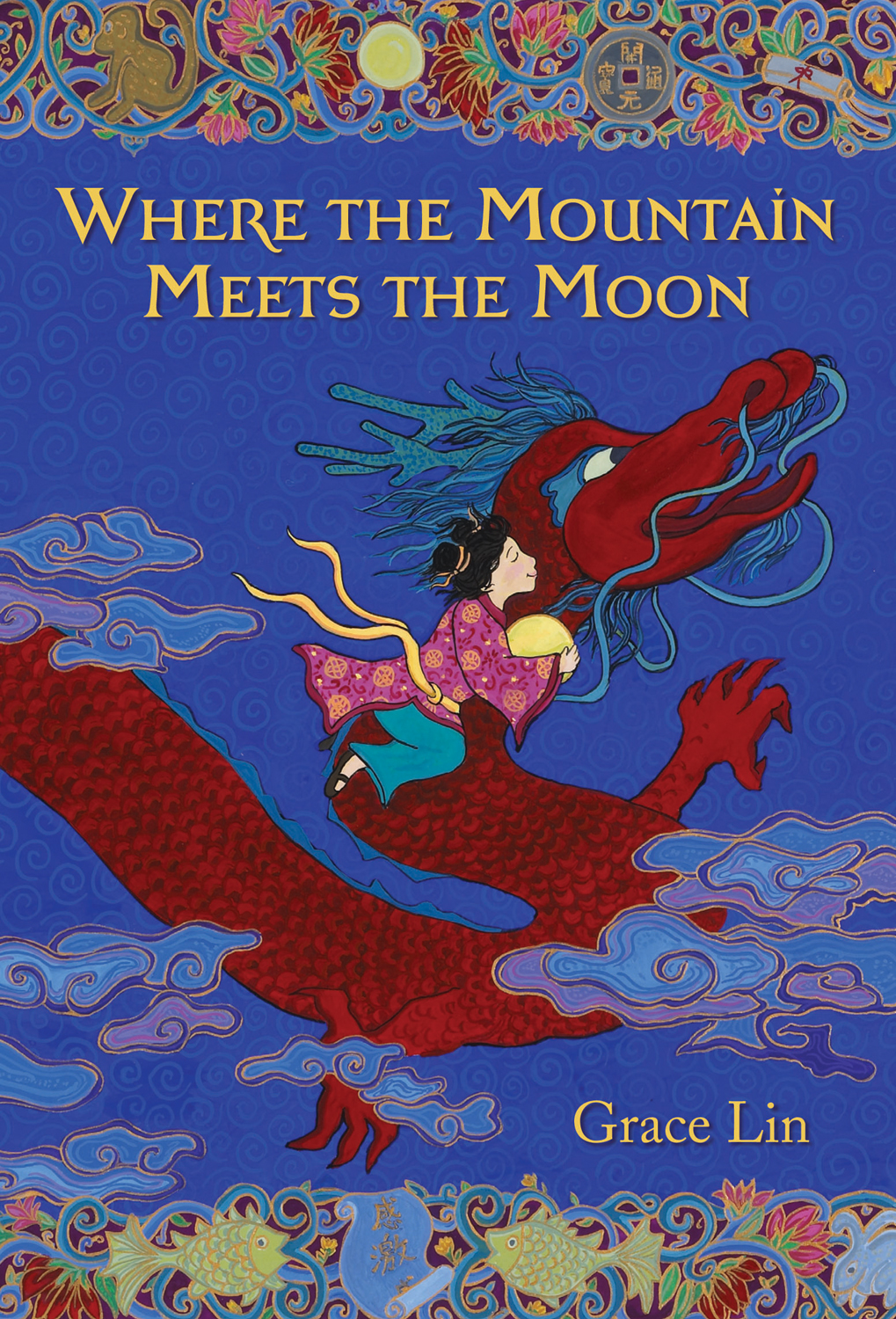

Grace Lin’s Where the Mountain Meets the Moon (2009) incorporates several well-known

Chinese folktales as part of its plot. Minli, a little girl from an

impoverished village located in a place called Fruitless Mountain Valley, goes on

a quest to see the Old Man of the Moon in an attempt to change the fortune of

her family. Along her journey she meets and befriends a friendly dragon who is

unable to fly. The dragon itself is a character from a famous folktale – about

a lifelike but unfinished painting of a dragon by a master painter which came

to life when the painting was completed by someone else – by drawing in the

dragon’s eyes. Minli and the Dragon decide to help one another – Minli in her

quest for fortune which she believed will bring her family happiness and the

Dragon in his quest for flight. Along their journey, they encounter several characters

from Chinese folktales, who each have their own stories to tell. All these

various characters and tales are skillfully woven into the fabric of the story.

Slide 9.1: Cover of

Where the Mountain Meets the Moon

Research

Research is a key factor in writing a good

book, we look at sources for Asian folktales e.g. unpublished stories on the

internet, newspaper articles and also books, old and new.

Books:

- Folktales from India

(1991) by A.K. Ramanujan

- Green Willow and Other Japanese Folktales (1987) by Grace James

- The Magic Boat and Other Chinese folktales (1980) by M.A. Jagendorf and Virginia Weng.

- Korean Folk-tales (1994)

by James Riordan

- Hikayat: From the Ancient Malay Kingdoms (2012) by Ninotaziz

- Malaysian Fables, Folk Tales and Legends (2012) by Walter Skeats and Edwin H Gomez

- Timeless Tales of Malaysia (2009) by Tutu Dutta

An excellent Internet source for World and Asian

folklore and myths (translated from the original):

For Malaysian folklore visit:

- www.sabrizain.org/malaya/library

Research for a book should not just focus

on one particular folktale but also on similar stories and variants of the

story. Reading a few versions of the same story will give you a feel for the

story.

|

| Illustration from Eight Treasures of the Dragon by Tan Vay Fern |

Slide 11.3: Photo of

water carrier

|

| The majestic Baobab of Madagascar |

Next, I refer to my books – The Jugra Chronicles - to explain this

process. To date two books have been published in the series:

*Miyah

and the Forest Demon (2011)

*Rigih

and the Witch of Moon Lake (2013)

The title of the series – The Jugra Chronicles – Jugra is the name of the old Royal

town in Selangor. But it is also the name of a hill on Carey Island (close to

Port Klang) and is considered to be sacred to the Mah Meri. I talked to a few

members of the tribe on a trip to Carey Island some years ago. In the books,

Jugra was a powerful shaman whose actions had repercussions on his descendents.

First of all decide on a setting for your

story – the place and time. When writing a story set in this part of the world

it is always wise to consider the two main trade routes of the past – the

overland Silk Route and the sea bound Spice Route. As we are right in the midst

of the Spice Route (The so-called Spice Islands have identified as the

Moluccas), it is natural to think of the Spice Trade.

I chose to set the story in Borneo, due to

the unique and diverse folklore traditions associated with the island –

including head-hunting and the use of magic! In the end, I narrowed it down to

a coastal region near Brunei - in the past, the Sultan of Brunei had suzerainty

over most of Borneo – and also because the two Malaysian states of Sabah and

Sarawak meets with Brunei and Indonesian Kalimantan here. The time period is

the 17th Century – over a hundred years after the fall of the Melaka

Empire. I did some research on the history of the area and came across the name

‘Tanjungpura’ and decided to use it in my story. The story is set against the

backdrop of a power struggle in Tanjungpura, an ancient trading with ties to

the Han Kingdom (China), Hindustan (India), Majapahit (Indonesia) and Melaka (Malaysia)

– which is now under the Dutch.

|

| Map of Borneo |

The protagonist is a girl called Miyah, whose father is the village Shaman. Her best friend is Suru, a girl whose father (a spice trader from the Han Kingdom who was once stranded in the village) has long since left the village. Miyah’s mother is the village mid-wife, a role which is also associated with magical abilities.

The story is as follows:

One morning, Miyah’s mother asks her to remain in the longhouse and look after her younger brother Bongsu as she had to go another village to deliver a baby. But it is a beautiful day and Miyah has promised to meet her friends at a waterfall upstream. Miyah disobeys her mother and joins her friends at the waterfall. A sudden sun-shower at the waterfall and the eerie cry of a bird, harbingers of misfortune, reminds Miyah of Bongsu. She returns home to find Bongsu missing! This part of the story – of a child who is lost in the forest and is believed to be abducted by an evil spirit is quite a stock part of native folklore in Malaysia and many other countries. The quest here is to recover a lost child rather than to look for treasure.

When Miyah returns, the village is also

strangely empty. Miyah has no one to turn to except Rigih, a boy who is an

outcast in the village because he came from another tribe. But he is related to

Miyah’s mother and agrees to help her. On the way to the forest, Miyah and

Rigih meets Sang Kanchil, the talking mousedeer, who leads them to Nenek

Kebayan (Nenek Kebayan is a central figure in Malay folklore, a little like

Babka from Russian folklore). Guided by the wise woman of the forest, they

embark on a quest to rescue Bongsu. They succeed in rescuing Bongsu but Miyah

is caught by the forest demon…

In the second book in the series, Rigih and

Bongsu’s attempt to rescue Miyah.

I also use another folktale – that of the seven

faeries who come down to earth to bath in a forest pool - to explain the origin

of Jugra and his magical powers. We also learn about the true nature of the

forest demon in this book.

Re-telling

a story

The stories in the book are ‘retold’ and

not ‘translated’. When you translate a story, you try to write it as close to

the original as possible, but in a different language. Retelling a story means

that this is your own interpretation of the story; with your own

characterization and your own dialogues and description. Even the chain of

events and sometimes the outcome of the stories can be changed sometimes,

although I prefer to remain true to the original story. I’ve read/heard most of

the stories in Malay but I try to understand (internalize them) them and then

re-tell them in my own words. It was a

little challenging especially when I come across words such as ‘huma’ etc and when

the original is in old Malay.

Yes, very often the same story appears in

several different versions. Usually I select one version but sometimes I

combine two or three different versions into one story!

The need to re-interpret and retell these

folktales, to make them relevant and appealing to a young contemporary

readership is the third key point. The author needs to balance authenticity

(being true to the story) with the need to hold the readers’ interest.

Pervasiveness

of Folklore

Folktales are quite universal.

A Malay folktale called Puteri Bunga Tanjung, which I have retold as The

Tanjung Blossom Faerie (it actually means Tanjung Blossom Princess), in Timeless Tales of Malaysia. This is the

story of seven faerie princesses who come to earth to take a bath in a

beautiful forest pool. The youngest sister loses her cloak or selendang and is

unable to return home. She sits under a tree and weeps and her tears turn into

fragrant blossoms when they touch the earth.

The lost fairy maiden is taken in by a poor

old woman – probably another Nenek Kebayan. The fairy helps the woman to make

fragrant flower posies and perfumed oil to sell in the village, but every

evening she returns to the forest to weep. As time passes, the old woman feels

sorry for the fairy and they search for the lost selendang so that the fairy

could return home. However, before she leaves, the fairy transforms the tree

she used to sit under into a Tanjung tree so that it bears night blooming

flowers which are shed at dawn, like the tears of a fairy.

|

| The Tanjung Blossoms - Mimusops elengi |

- Regarded as a national folktale, this particular folktale clearly originates from Penang as Tanjung is the old Malay name for Penang. There are also similarities with another folktale, Bunga Tanjung which is known to originate from Penang. The bunga tanjung (Mimusops elengi) is a fragrant, night-blooming flower.

This motif of the seven fairy sisters

taking a bath in a pool appears in folktales in Japan, Korea and China. In

fact, in Ruth Manley’s Peony Lantern,

there is a character called O-Kuni and her travelling troupe of dancers. It

later turns out that she is actually a fairy trapped on earth because someone

had stolen her magical robe of feathers!

|

| The Weavermaid and the Herdsboy |

flock of seven cranes land on the shores of a lake or forest pool. The cranes turn into maidens who hang their robes on the branches of a tree before going for a swim. The fisherman hides one of the robes so that one of the fairies is trapped on earth. The fairy is forced to marry the fisherman and lives with him and his mother for many years. Eventually, when everyone seems to have forgotten that she is in fact a fairy, the mother accidently comes across the robe of feathers which the fisherman had hidden and decides to air it. The fairy asks if she could try it on and she turns into a crane and flies away!

Even more surprising, this same motif of

seven fairy sisters appears in an Iban legend called ‘Jelenggai’, also found in

the Timeless Tales of Malaysia collection.

Even more surprising, this same motif of

seven fairy sisters appears in an Iban legend called ‘Jelenggai’, also found in

the Timeless Tales of Malaysia collection.

Another variant to this folktale is that of

Manohra, the bird Maiden. Retold in my book, Eight Jewels of the Phoenix, this is the story of seven princesses

who are bird maidens. As before, they take a bath in a secluded forest pool,

however the youngest is captured by a hunter who gives her as a gift to the

prince of the Kingdom. The prince falls in love with Manohra and so on… The

story of Manohra is widely known in the East Coast of Peninsular Malaysia and

is definitely of Thai origin as there is a classical Thai dance drama based on

this story. Manohra is also widely known in Cambodia and Laos and the origin of

this story is more likely to be from India.

So from studying folktales we can see that

stories travel all over the world!

References

1.

Divakaruni, Chitra Bannerjee

(2005), The Mirror of Fire and Dreaming,

published by Roaring Brook Press, Connecticut, United States of America.

2.

Dutta, Tutu (2009): Timeless Tales of Malaysia, published by

Marshall-Cavendish Malaysia.

3.

Dutta-Yean, Tutu (2009): Eight Fortunes of the Qilin, published

by MPH Group Publishing Sdn Bhd, Malaysia.

4.

Dutta-Yean, Tutu (2009): Eight Jewels of the Phoenix, published

by MPH Group Publishing Sdn Bhd, Malaysia.

5.

Dutta-Yean, Tutu (2011): Eight Treasures of the Dragon, published

by MPH Group Publishing Sdn Bhd, Malaysia.

6.

Dutta-Yean, Tutu (2011): The Jugra Chronicles: Miyah and the Forest

Demon, published by MPH Group Publishing Sdn Bhd, Malaysia.

7.

Dutta-Yean, Tutu (2013): The Jugra Chronicles: Rigih and the Witch of

Moon Lake, publishing in progress by MPH Group Publishing Sdn Bhd,

Malaysia.

8.

Garner, Alan (1967): The Owl Service, first published by

William Collins Sons & Co. Ltd, Great Britain.

9.

Jagendorf, M.A. and Virginia

Weng (1980): The Magic Boat and Other

Chinese Folktales, published by Vanguard, New York, United States of

America.

10.

James, Grace (1987): Green Willow and Other Japanese Fairy Tales,

published by Avenel Books, New York, United States of America.

11.

Lewis, C.S. (1950): The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe,

published by Goeffrey Bles, United Kingdom.

12.

Lin, Grace (2009): Where the Mountain Meets the Moon, published

by Little, Brown Books for Young Readers,

New York, United States of America.

13.

Manley, Ruth (1978): The Plum Rain Scroll, first published by

Hodder and Stoughton (Australia) Pty Ltd, Sydney, Australia.

14.

Manley, Ruth (1982): The Dragon Stone, first published by

Hodder and Stoughton (Australia) Pty Ltd, Sydney, Australia.

15.

Manley, Ruth (1987): The Peony Lantern, published by Hodder

and Stoughton (Australia) Pty Ltd, Sydney, Australia.

16.

Ninotaziz (2012): Hikayat: From the Ancient Malay Kingdoms, published

by Utusan Publications, Malaysia.

17.

Ramanujan, A.K. (1991): Folktales from India, published by

Pantheon Books, United States of America.

18.

Skeats, Walter and Edwin H.

Gomez (2012): Malaysian Fables, Folktales

and Legends, published by Silverfish Books Sdn Bhd, Malaysia.